Documentation of historic grand pianos of Klassik Stiftung Weimar

It was an honour to document several important instruments of Klassik Stiftung Weimar as part of a „KUR-Programm zur Konservierung und Restaurierung von mobilem Kulturgut (gefördert durch die Kulturstiftung des Bundes und die Kulturstiftung der Länder 2007-11)“ :

The objects:

Weimar 1798 *

Paris 1812

Vienna 1825

Marseille 1845/46 **

* source: https://suche.klassik-stiftung.de/#/details?id=/resources/id/object/museen/223349

** source: https://suche.klassik-stiftung.de/#/details?id=/resources/id/object/museen/223771

- anonymous grand piano in the tradition of Johann Andreas Stein.

During documentation identified as an instrument of the Stein-disciple Johann Georg Schenck, Weimar 1798 - Grand piano by Sébastien Érard 1811/12 of Grand duchess Maria Pavlovna.

According to company records completed within the last days of the year 1811 but delivered after New year with remark in the front plate 1812, afterwards manually altered to"1802" - Grand piano by Nannette Stein/Streicher c.1825 from the Weimar court chapel

- Grand piano Jean Louis Boisselot, Nr. 2800 1846, former possession of Franz Liszt

Little is known about the early history of the Schenck grand. As a local instrument it might have been produced for a local buyer; local lore and the later placement at the Widdumspalais Weimar associated the instrument with the piano culture at the time of Duchess Anna Amalia of Sachsen-Weimar but no further evidence could be unearthed, but it was indeed located at the Weimar court, maybe temporarily used in the court theatre. Its construction reveals the spread of techniques and ideals linked with Johann Andreas Steins by his disciples.

The Érard grand was acquired for grand duchess Maria Pavlovna for Weimar Schloss castle,

where it was for personal use of the grand duchess as a platform for her wide collection of piano music (preserved in HAAB

Weimar) and for chamber music at its historic place, the cedar apartment of Weimar castle. It is undoubtedly a luxury object in Empire style. Comparable instruments in this design are preserved in Amsterdam from the possession of the Dutch king Louis

Bonaparte and in Stockholm from the possession of the Swedish royal family Bernadotte.

The Streicher grand has close link to court chapel director Johann Nepomuk Hummel and the musicians of the Weimar orchestra, in particular the Eberwein family. The instrument was used intensively showing hollowed key covers.

It represents the preference for Streicher grands, established by Hummel in

Weimar, from his service instrument acquired in 1819 and popularized by his image as an interpreter of the music of Mozart und

Beethoven and his fame as a piano teacher. Goethe's choice of a Streicher grand, played by Felix Mendelssohn

Bartholdy for Goethe, also reveals this influence.

Paris 1812

Vienna 1825

The Boisselot grand was used by Franz Liszt during his last leg of his grand tour 1846/47 and for composing during his Weimar years. The transport from Marseille to Istanbul, then north into modern Ukraine and further on to Weimar left its traces and made it unsuitable for public concerts, but it meant a lot for Liszt who met his beloved Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein at his concert in Kyiv 1847. Whether the famous visitors at Liszt's in the Altenburg like Berlioz and Wagner were permitted to see this instrument kept in private, is unknown. With the aid of this instrument the most eminent part of Liszt's compositions took shape and he declared in a lettter to Xavier Boisselot: „Obwohl die Tasten durch die Kämpfe der Musik in Vergangenheit, Gegenwart und Zukunft fast abgenutzt sind, werde ich dem Vorschlag, es auszutauschen, niemals zustimmen und habe mich dazu entschlossen, es als bevorzugten Arbeitskollegen bis zum Ende meiner Tage zu behalten.“ („Though the keys suffered and worn in the musical battles of past, present and future I won't agree to any proposition to change it and have decided to keep it as a preferred companion at work to the end of my days“ letter dd. 3rd Jan 1862; in: Adrian Williams (ed.): Franz Liszt: Selected letters, Oxford, p.572.)

These grands are closely linked to cultural life of the Weimar classical era and its music, and not only via their users but also their listeners. It may be assumed that the Érard grand as well as the Streicher grand gave Goethe inspiring and emotional music experiences. Beethoven's music might have transmitted on the Streicher grand played by Hummel impressions that found their reflections in Goethe's ideas on this music. The Boisselot grand became Franz Liszt's valued musical tool for his eminent part in piano culture. So the sound idea and playing structure are an important link to the perpetual changes of musical interpretation.

Since instruments are not a automaton but a framework for ideas, in the technical structure and designs of the action poetical ideas take form. These instruments from 1798, 1812, 1825, and 1846 represent a paradigmatic change of sound ideas. Each has a different action: the Schenck grand a German action after Stein, the Érard grand a (later slightly modified) pulling action after his own design of 1807, the Streicher grand a Viennese, the Boisselot grand an English action. This exemplifies the vivacious variety of musical esthetics and interpretation in the first half of the 19th century, which could raise doubts about modern uniformity.

Documentation and archive research

The project included documentation of the instruments and archive researches.

The musicological research was done by Prof. Dr. Franz Körndle and PD Dr.

Erich Tremmel, photographic documentation by Helmut Balk.

(See :

http://www.musik-heute.de/2947/liszts-geheimnis/).

The results of these researches, concluded by the Thüringer Landesausstellung 2011 "FRANZ LISZT - Ein Europäer in Weimar", were published in the following:

- Franz Körndle and Gert-Dieter Ulferts (ed.):

Konservierung und Restaurierung historischer Tasteninstrumente in den Sammlungen der Klassik Stiftung Weimar

(Augsburg: Wißner-Verlag, 2011)

- Erich Tremmel and Gert-Dieter Ulferts (ed.):

Kosmos Klavier. Historische Tasteninstrumente der Klassik Stiftung Weimar

(Augsburg: Wißner-Verlag, 2011) - Detlef Altenburg (ed.):

FRANZ LISZT - Ein Europäer in Weimar; Katalog der gleichnamigen Thüringer Landesausstellung Weimar 24.6.-31.10.2011 (Köln: Verlag Walther König, 2011)

some Instrument details

Details grand by Sébastien Érard 1811/12

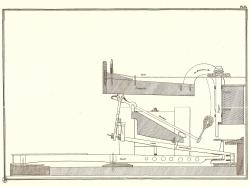

Drawing of the action of Erard's (denied) privilege of 1807. Later the Weimar instrument got the hammer shank beaks shortened, probably to achieve a more direct and steadier attack.

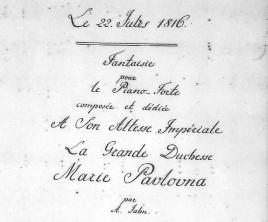

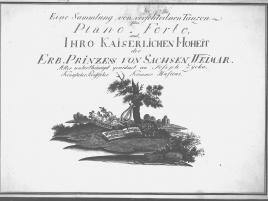

Examples of piano works dedicated to Grand duchess Maria Pavlovna (in Weimar, Anna Amalia Bibliothek) played on and possibly designated for this instrument.

The following pictures show single high precision elements of the Weimar grand but also the reshaped hammer shank beaks and further damages and repairs of the instrument over time.

action parts Nannette Streicher grand 1825

grand piano by Louis Boisselot, Marseille 1845/46

signature Boisselot grand

1844 is not the year of production of Liszt's grand!

A technical specification of this grand is Boisselot's bottom spreader bar – a not very suitable means to counter the strings' pulling force.

grand by Georg Schenck, Weimar 1798

The action of the Schenck grand has wooden hammer heads without leather cover which is a very rare feature with grand pianos.

Whether this is an initial feature or a later uncommon modification could not be established without doubt.

Traces of abrasion at the surfaces of the hammer heads reveal a time of temporary use in this state for some time.

The oldest grand of Klassik Stiftung Weimar without an outward signature believed by an anonymous maker could be identified with endoskopic research showing a manuscript pencil signature on the inside of the base board as made in the workshop of the Weimar Stein-disciple Johann Georg Schenck in 1798.

The complete signature (on the picture just part) is:

"Joh Georg Schenck / à / Weimar / 1798 / im Monath Julii"