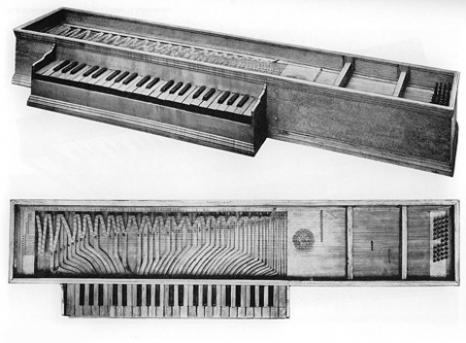

The Fretted clavichord

Fretted clavichord, Nuremberg or Leipzig, around 1540; Museum of Musical Instruments of the University of Leipzig

This early clavichord clearly demonstrates the advantages of the fretted clavichord: the instrument required far fewer strings than it had notes, allowing it to be tuned in a short amount of time. It required minimal space, could easily be transported, and placed on any table for playing.

Music Example:

Excerpt from Matthias Greiter (1495-1550) "Verschütt hab ich das Habermus"

(from the tablature of Clemens Hör)

played by René Clemencic

Instrument: Peter Kukelka, copy of a fretted clavichord circa 1540

Fretted clavichords are among the oldest keyboard instruments in a still playable condition. Their basic construction is simple, the individual components relatively indestructible, and the instrument itself is both space-saving and economical in terms of maintenance and tuning effort. This is because certain tones that are usually not used simultaneously in music were "bound" to one set of strings (such as C and C-sharp or B flat and B natural), so when tuning one set of strings, several notes were adjusted at once. This also allowed the instruments to be built relatively small and light, thus somewhat mitigating the "deficiency" of all clavichords: their very quiet sound.

They were the ideal instruments for domestic, private music-making and thus also for practice. So quiet that no one in the vicinity was really disturbed, yet the direct touch allows for very sensitive playing and audible control over the activity of the fingers. The clavichord forgives nothing: if you strike too hard, you press too strongly on the strings, causing them to rise in pitch—a distinctly audible "whining" of the tone would signal the need to refine one's touch in the future.

However, as early as the 16th century, it became apparent that in some countries where keyboard music was highly "audience-oriented"—for instance, when it was explicitly embedded in a larger social context, such as dance or entertainment music, or to accompany singers or instrumentalists—the use of the clavichord declined. It was simply too quiet for such purposes, and by its construction, it couldn't be made loud enough to fill even a larger room.

Therefore, the instrument was hardly in use in Western Europe; in France, England, or Spain, and later in Italy, it disappeared from music life between about 1550 and 1650. In contrast, it remained in use in Germany and Scandinavia until the early 19th century.