Organ design and architecture

The internal design of any organ is determined by technical requirements in combining the principal components of wind distribution, linking keys and valves and pipe placement.

Of further importance are planned position of the instrument, static, and lighting. But besides the necessity to place the pipes inside one or several cases to keep them safe from dust, damage, not to forget theft, an organ builder in the Baroque had a wide range of artistic freedom to design the organ case and front.

The visible pipes in the front constituted an important design element. Usually pipes of the „Open diapason/Principal“ design were made of pure tin or a tin-lead alloy with a minimum of lead in most countries. The silvery shine of these pipes contributed to a decorative appearance, unless not camouflaged under decorative painting to hide the use of cheap pipe material.

In the early stages of organ construction the pipes were placed according to sequence of keys (Fig. 1). This was considered esthetically insufficient when the bigger the instruments grew in the late middle ages. The first solution was a mirror image placement of pipes with the biggest (and lowest) pipes in centre, the smaller ones places decreasing to the outer edges (Fig. 2)

A symmetrical pipe placement in the front in considerable distance to the wind chest and divided in a „C row“ to the one and a „C# row“ to the other side created the necessity how to deliver the wind to the proper pipes. This problem was usually solved by wooden air ducts for every single pipe (Fig. 3)

A second design element was further grouping the pipes in protruding towers or flats, symmetrically around the central axis of the façade, lowest pipes in towers, smaller in flats, either as a central tower or two towers at the outer edges (Fig. 4). If the organ builder could only manage the wind distribution via air ducts the design options for the façade were almost limitless. Only under very few circumstances an organ builder had to use dummy pipes if hanging pipes or a „sun“ of pipes in a circle were desired.

More design options included the placing of pipe fronts in straight line or protruding in triangle, circular or trapezoid lines. The next possibility was varying the length of pipe feet: When traditionally the pipe feet were of equal length the labia gave the visual appearance of an almost uninterrupted dark horizontal line in contrast to the bright rising pipes. If, however, deeper pipes got shorter pipe feet, the pipes could be made as if of same length throughout, or, in showing counter-moving lines of labia and upper ends giving the façade a sublime appearance.

Another design element in the juxtaposition of the pipes is the position of the labia. If, as was customary for a long time, the pipe feet were made of equal length, the labia formed a dark horizontal line appearing almost continuously from a distance, giving an effective optical contrast with the vertical pipes. On the other hand, this line could also be put in motion with pipe feet of different lengths, often in such a way that shorter pipes received longer pipe feet (and thus higher labia). The result could then appear as pipes of the same overall length were standing and a horizontally uniform upper edge; the necessary differences in sounding pipe length could be compensated with longer pipe feet for higher pipes. Another possibility (with a similar procedure) was an opposite sequence compared with the upper pipe ends, which increased the monumentality of the deep pipes placed in the center.

However, the pipes, their arrangement and the sequence of labia did not form the only design elements of an organ front. Especially in the period of the baroque, equally in love with symmetry and ornament, no organ was conceivable without its wooden or stone casing with architectural elements, a more or less differentiated colour setting and plant-like veneers (Acanthus) conceivable. Latin American organs, for example, were painted particularly decorative and colourful (Figures 5, 6, 8).

Occasionally even the organ pipes themselves were coloured (esp when organ metal of lower tin content was used), which became a typical stylistic feature of English organs (Fig. 7).

Not infrequently, sculptural decorations were added, or the traditional organ wings (gradually out of fashion), or, more often, pierced carved veils, tendrils and garlands of wood. For most of this special decoration, however, sculptors or painters were contracted.

There were, however, enormous differences in the ways of overall design. In some regions, organ cases were generally preferred, which resembles the internal structure of the organ and its division into separate organ parts, others prefered richly ornamented cases blending in the entire interior design. The latter in particular were often perceived as controversial and neglecting the proper nature of the organ, but baroque organ building can hardly be understood without the typical but also eccentric design ideas of the time.

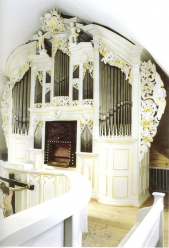

In the second half of the 18th century, however, the general artistic taste became a little more sober: the approaching neoclassicism sought the monumental effects of ancient art and replaced the manifold curved and colourful decorative elements of the Baroque by borrowing from Greco-Roman symbols and ornaments in mostly plain, pure white (Fig. 9, 22).

The choices of such design elements is often typical for certain epochs, landscapes or even certain organ builders and in some cases allow conclusions about the origin, education or aesthetic preferences of individual organ builders; occasionally this also helps in the attribution of anonymous instruments to their alleged builders.

On the other hand, the organ housings of some organ landscapes, such as in France, but also in Italy, are often very uniform. For example, the organ of Thomas Dallam in Guimiliau in Normandy (Figure 10) and an organ of the same size by Andreas Silbermann, such as that in Ebersmünster (Figure 11) east of the Rhine, hardly differ from each other on the outside; but in the first case the typical French case houses in its interior an organ in the English style, in the other case an instrument that represents a synthesis of German and French traditions.

Many design questions ultimately depended decisively on the location of the organ within the church. The traditional site of an organ on a swallow’s nest gallery on a nave wall (Fig. 12) played only a little role in the 17th and 18th centuries. Such galleries offered little space for the organ itself. lest alone other contributors. The placement of an organ on a choir screen (Fig. 13) between the choir and the nave was also rare. As a peculiarity, such organs usually have a double front on both sides.

Hardly ever an organ builder was able to place an instrument almost centrally in the room. A rare example may be St. Ludgeri in Norden, where the organ was placed around a wall edge of the crossing, with the manual organ facing the transept, the pedal tower placed to the side facing the main nave.

As a rule, in many Lutheran churches the organ was installed on the east side, in the vertical main axis directly above the altar and pulpit (Fig 14, 15). This gave the organ its own share in the proclamation of the faith and thus also a special theological significance. This positioning of the organ promoted the tendency to a design with a significant emphasis on the central axis, which continued the vertical staggering of the altar and pulpit towards the sky.

In Catholic churches, on the other hand, the western side was usually preferred. There was often, however, an architectural conflict with the west window, which was not only an important element of the exterior and interior church architecture since the Gothic period, but was also generally indispensable for the light inside. The organ should not obstruct the incidence of light as much as possible and would not bear any direct sunlight itself. Placing the organ directly in front of the window was therefore only possible in rare cases - for example, if a tightly enclosed church was only given indirect light (Fig. 16).

The solution to this dilemma was to build the organ around the west window. One of the first organs to solve this problem was the famous organ by Jan von Dubrau in the Fugger Chapel of St. Anna in Augsburg 1513, whose center was recessed in a half-circle alongside the lower edge of the western window.

Later organ builders began to divide the organ around the west window or windows into severals cases. Depending on how many windows the façade had at gallery height, this often meant developing shapes that only occupied a small wall area, but still provided sufficient space for the large pedal registers. In this consequence, the main organ of the collegiate church in Zwettl offers an extreme, but nevertheless very logical example (Fig. 17): Around the window are two cases opening obliquely to the church, which contain the pedal registers. The manuals, on the other hand, are housed in the extremely voluminous parapet case here and do not significantly impede the incidence of light.

Following the example of the Egedacher workshops, the division into several cases became the norm for larger organ works - even if there was no window at all, as was the case with the main organ of Herzogenburg (Fig. 18) with a mock architecture painted in perspective in the centre of the gallery.

The situation for the organ builder could become more complicated when several windows were to be avoided. Joseph Gabler’s organ arrangement in Weingarten, forced by no less than six windows in the western facade of the monastery church, does not in the sense possess one organ case, but six; two high towers to the left and right of the centre and two further cases at the outward edges contain the main organ and a part of the pedal with the imposing pipes of the contrabass 32' in the middle, plus two corresponding parapet cases with the positive and another part of the pedal. Three bridge panels extend between the rear parts of the housing, and the crown organ contains further registers above the upper middle window. The organ thus occupies almost the entire wall surface, in addition a good part of the parapet, but the light guidance remains properly guaranteed; only the free-standing keyboard as well as the hanging "grapes" of the pedal chimes obstruct a small part of the lower centre window (Fig.19).

A whole series of organ builders followed the model of the Weingarten organ, such as Andreas Jäger (Fig.) at the main organ of St. Mang in Füssen (Fig. 20; 5 windows) or Balthasar Freywiß (Fig. 21) in Irsee (1 large window, above it a crown positive) and Johann Nepomuk Holzhey (Fig. 22) in Neresheim (6 windows; a neoclassicist version of the Weingarten design).

All these factors together testify that the exterior design of an organ represented an aesthetically quite significant task for the artists involved in the construction. The appealing execution of the organ case in harmony with the other interior design of the church space was usually also a special concern for the clients, and so it does not surprise in the end, when far more organ cases have been preserved from the Baroque than the actual organ works inside. The aesthetically successful casing of the instrument as an unmistakable design element of the church space has acquired considerable intrinsic value over time. Nevertheless, a viewer and listener occasionally may find it deplorable when the sound of a possibly mediocre organ of later times emerges from an artistically outstanding historical organ case. The more delight when the qualities of the view and sound of a historical organ correspond to each other in one of the rare monument organs.